Custom Build: a Chance to Choose

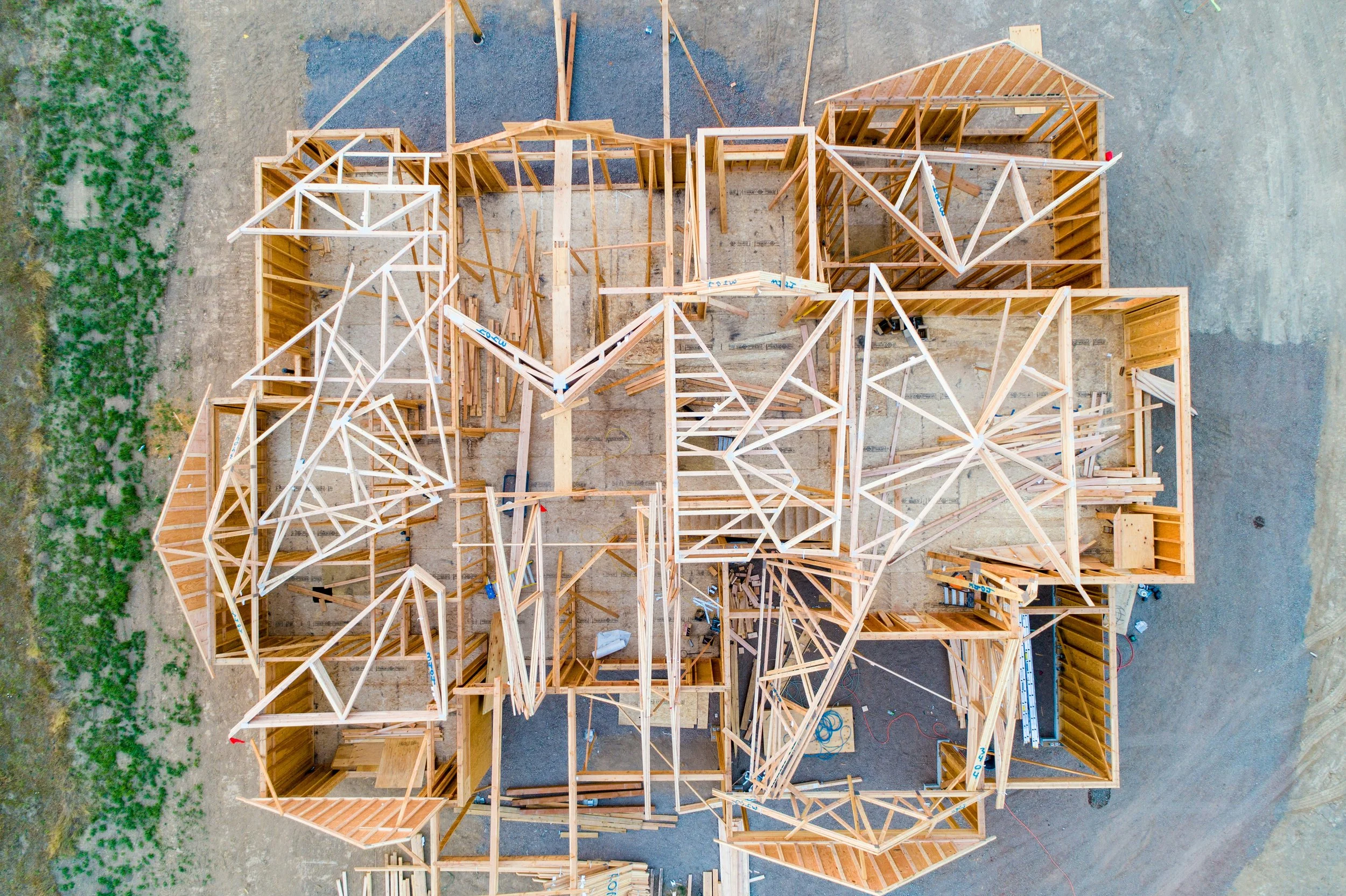

Photo by Avel Chuklanov on Unsplash

Custom Build is a way to create an individual home. The idea of Custom Build is that the Homebuyer buys the plot and instructs a housebuilder to build a house for them. The Homebuyer has the opportunity to design and specify the home. A chance to choose.

Britain has a poor record when it comes to Custom Build. In many countries in Europe, the US and Australia, a great many new homes are commissioned by those who will live in them. In Britain some 73% of new homes are built by a small number of national housebuilders.

No wonder then that Government wishes to change this. It wants to input more individual design into new housing. It has required all local planning authorities to provide a self-build/Custom build register of residents wishing to buy building plots. It has offered tax incentives to those wishing to custom build.

What has always been a hinderance to Custom Build is the lack of suitable plots. Now with the right to register, there is the opportunity to see more plots available for custom builds. Planning authorities are granting planning permissions limited to Custom Build.

A further limitation to the concept of Custom Build is that building plots often come in multiples. This means that any site with more than a single plot will require communal work of some kind. Works that are not related to any one plot but are essential to service the estate. Demolition of an existing building, surveys, estate road, drainage, services, landscaping are all matters that may need to be dealt with to ensure that the plot buyer buys a serviced plot.

These communal works are undertaken by a Development Manager. He provides the essential serviced package such that each individual plot is ready to build. The plot buyer buys the plot from the Landowner with a simultaneous service package at an additional cost from the Development Manager. Having bought the plot the plot buyer may wish to alter design of the home and the Development Manager will assist with advice as to what is practical.

There are two advantages often available to the plot buyer. First SDLT (stamp duty) is only charged on the plot price, not the end value of the completed home. Also Custom Build is exempt from community infrastructure levy.

The Development Manager will offer a building contract for the new home when the design and specification are finalised. This might be at a fixed price, a cost plus contract or the supervision of works undertaken by a selected timber frame package company. There is adequate opportunity for variations too as plot buyers often wish to make small changes as work proceeds.

The Outline planning permission will give an indication of the limitations to design and specification but the plot buyer will have the chance to choose many materials and fittings in the new home. Matters such as kitchens, bathrooms, floor finishes, garden and landscaping and the design of internal room layout to suit each family’s needs. Building brand new gives the best opportunity to ensure energy efficiency to reduce ongoing costs. The Development Manager will advise what renewable energy sources suit best.

Custom Build could be the future for new homes. It beckons the way for creative design, improved quality and energy efficiency. It really is a chance to choose.

Denis Minns is the author of Projects in Property: the business of residential property development. Bath Publishing.

Are we more planned against than planning?

Is the sheer complexity of the planning system an obstacle to providing new homes? It may well be, says Denis Minns.

In his seminal book Outline of planning law, author and planning lawyer Sir Desmond Heap paraphases King Lear in asking whether we are ‘more planned against than planning?’ It has indeed seemed to me at times that planning is more about development control than planning new and vibrant communities or even allowing minor additions to existing houses. Have we been planning, or inventing ways of restricting development in the belief that new development will detract from our existing environment? Has this philosophy led to our present housing crisis? Are we more planned against than planning?

I believe now that attitudes are changing. Government and local planning authorities have finally got the message that a more proactive approach to planning is required to deliver more homes. This change in outlook will no doubt be welcomed by planners who have a key role in the proactive planning process, but it comes with an increasingly heavy burden that demands creative and organised professional skills together with a whole range of additional responsibilities and potential constraints.

Today, planning applications for development require many reports and surveys that are often technical in content. The effect of these needs to be understood to ensure that their strict interpretation will not contradict the implementation of the permission. These reports often include: ecology, arboriculture, archaeology, heritage, hydrology and environmental matters relating to contamination of soil. The planner has to be able to understand the requirements of this supporting information and balance those requirements with design, density and access arrangements in weighing up the benefits of a proposal.

It is no surprise then that this welter of information increases the time taken for local planning authorities to decide planning applications and can introduce reasons for refusal that are outside the traditional planning brief. Has this now circumscribed the desire to grant consent for more new homes?

The number of conditions that many planning permissions are subject to has increased due to the supporting information. This is particularly true of listed building consents. I have seen conditions on planning applications that make implementation within the specified timescale impossible. The task of balancing the requirements of the supporting information with a timescale for implementation of the planning permission is certainly not an easy one.

The sanctity of green belt has often seemed to me to be misplaced against a background of acute housing need. I do not see that we will achieve our housing targets without release of green belt land. The favoured school of thought here is that we should concentrate green belt release around railway stations. This seems to me an initiative that addresses two issues. First the creation of affordable new homes but also the reliance on rail travel rather than car use. Planners will grasp this as an opportunity to increase density of development and pedestrian pathways rather than vehicle use. The challenge here is the inevitable opposition from local residents and national groups keen to preserve green belt that the planner is faced with.

While release of green belt sites introduces a solution to our need for more new homes, a whole range of supplementary interests evolve. New developments are often criticised as an impact on medical services in a community. The solution here is the opportunity to create medical centres within the new development. Indeed, new housing development might promote public health via pedestrian circulation, cycleways, sports facilities and community groups. Local shops and offices serving the new housing and providing employment can be incorporated. Here the results of housing need surveys and pressure for speculative housing is balanced against a demand for employment and community infrastructure. All these requirements place an additional demand on planners who have to delve into statistics to achieve balanced proposals.

Permitted development used to be limited to minor household development such as small extensions, patios and garden walls. Today it has been expanded to include a whole range of potential changes of use to provide more homes, and further changes are envisaged that will allow us to provide new homes. This is a positive move by government and one that planners will welcome as such decisions are often free of the restrictions of conditions. This fluid and rapid change does, however, create issues with some developers taking advantage of the absence of space standards but it is an initiative that demonstrates the ability of the planning system to be more flexible and free from additional constraints.

A variety of tax measures have evolved that require developers to contribute to the community. Planning agreements and community infrastructure levy are useful tools for planners when granting planning permissions to fund the improvement of infrastructure such as highway works, local schooling and community facilities. These measures again place an additional administrative burden on the planning system.

This article was written by Denis Minns for The Planner and reproduced here with permission.